THE County Gazette would have been laughed out of town if, when it first hit the streets in 1836, it had tried to launch a #talkupTaunton campaign.

There are so many wonderful things to crow about in our town today, which led to our decision 183 years on to run our well-received #talkupTaunton initiative, which even won praise last week from Tauntophile Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson.

But 1830s Taunton doesn't appear to have been such a great place to live in if a book written 30 years later by lifelong townie Edward Goldsworthy is anything to go by.

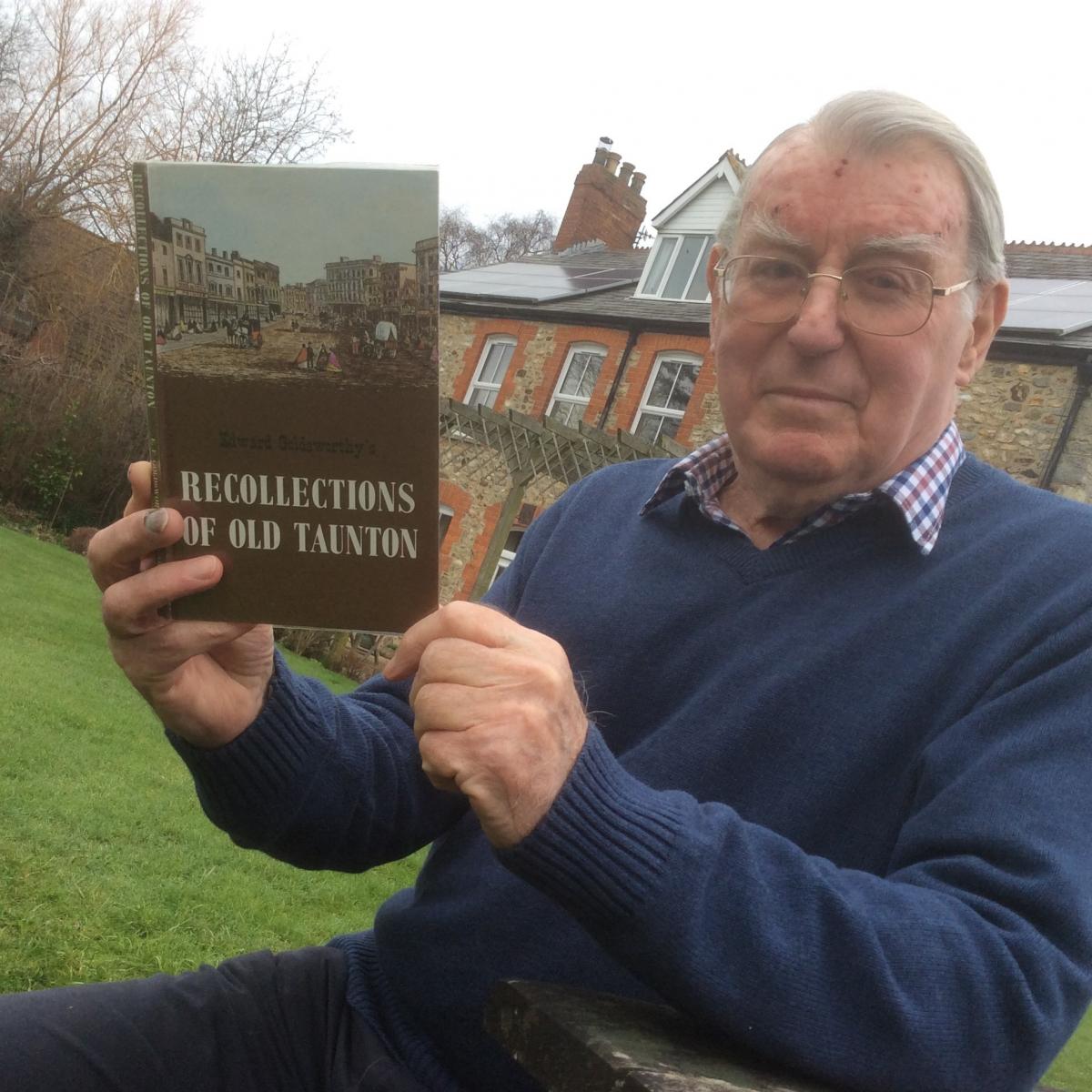

I am grateful to Alan Reeve for bringing Recollections of Taunton to my attention - and equally grateful I never had to live through some of the stories Goldsworthy recounts.

As Alan points out, his family had lived locally for more than 400 years, with Edward resident from his nappy days in 1817 until his death in 1896. He trained as a pharmacist and ran a business in the town he loved for more than 30 years.

Here's a taste of his tour-of-the-town book charting anything and everything he recalled in later life of his younger days.

"Silver Street was a dirty and very immoral place, noted for the residence of a class known as 'The Great Social Evil'."

Most of the houses in East Reach were thatched and, as a consequence, "fires occurred there pretty often".

Mount Fields was a "battleground where both men and boys decided their quarrels", while in summer Shuttern "usually had a dead dog or cat, an old kettle or spranker lying between the stones".

Westgate Street was "full of rubbish", North Town was "low, dirty and damp" and people struggled to sleep with the incessant noise of crows and seagulls, half a dozen of which fell victim to the author's grandfather's shotgun.

Going into one of the scores of pubs listed in the book wasn't always a safe idea, with the landlords of the White Hart, in Station Road, and the Black Boy Inn, in Canon Street, both suspected of murder.

Goldsworthy recounts seeing "all the abominations" from the courts passing an open drain in Bath Place, while the 100 people employed in the town bridge area were "the roughest and coarsest lot".

Crockford, the headmaster of a school in Church Square, "had quite a relish for caning" boys "without the slightest cause". After the thrashings he would "rub his hands, stiver up his short hair, and look quite angelic".

Anyone standing outside St Mary's Church on a Sunday morning would witness "the singing of psalms" on one side and "cursing, fighting and blaspheming" on the other.

Fisticuffs appear to have been a popular leisure activity - there's the story of a blind man and his friend with a club foot coming to blows after falling out, election campaigns descending into violence and drunks "wrestling, rolling bloodied in the gutter".

There was a "medical gentleman" who knew how to "use his fives" and a man called Bob who smacked a commercial man to the ground - the latter complained he hadn't even spoken to his assailant, who replied: "Why did you not speak?"

Goldsworthy's brother, Joe, had half a dozen rounds with Kit Spencer at which point the latter asked why they were fighting - Joe replied: "I don't know", upon which they shook hands and parted.

Taunton's rich amused themselves "eating, drinking, smoking and gambling" until they fell out of their chairs, passers by were not disgusted by the "immoral songs" sung in the streets, there were "indecent pictures" in barbers' shops, some areas stank from open sewers and the poor had a "horror of soap and water".

Alan once gave a talk on the religious aspects in the book, with six churches and 12 other places of worship in the town.

After the tower at St Mary's collapsed, it cost £6,217 to rebuild from 1858-62, while the bill to replace the tower at St James after it was declared unsafe came in at £4,002 5s 5d.

While St Mary's vicar was a "jolly, outspoken, good tempered person", its gravedigger was "short, stout, gloomy and sour - and looks at everyone as though he would like to dig his grave" and an "official mourner" turned up at funerals despite rarely knowing the deceased.

Temple Chapel preachers were "neither learned nor eloquent" and Goldsworthy was once nearly thrown into the coal hole there for "shooting peas during service".

Goldsworthy attended the opening of the Bridgwater to Taunton Canal, but left early as it was "freezing cold and wet".

He tells of his Uncle Jack, who fought at Waterloo, but came home "battered, demoralised and totally unfit for a quiet and peaceful life"

But it wasn't all bad - North Town's annual four-day fair and Taunton Races at Mountlands were popular - even if thieves were busy stealing purses and silver tankards.

Many thanks to Alan Reeve for his contributions and for the information that Edward Goldsworthy is buried under a yew tree in a family grave in the churchyard at Trull.

One last observation - Taunton 200 years ago wasn't the nicest of places. Our lovely town in 2019 isn't perfect, but next time you're tempted to run it down, thank your lucky stars you were born in these modern times.

Let's #talkupTaunton

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel