On the 75th anniversary of D-Day, Michael Ford remembers the BBC war correspondent from Wellington who reported from the beaches of Normandy.

FRANK Gillard, from Poole, near Wellington, was one of the BBC’s most distinguished war correspondents.

I was privileged to meet him twice –once when I profiled him for the County Gazette and, again, when I was a producer at Radio 4 making a programme on the 50th anniversary of D-Day.

The son of a Rockwell Green farmer, Frank attended Wellington School and later taught science at Priory Secondary Boys’ School, Taunton, before joining the BBC early in the war as a correspondent with Southern Command.

Soon he was reporting alongside General Montgomery - a friendly, discerning commander, Frank remembered, short with piercing eyes.

'Monty' was used to having Frank Gillard around – he’d covered the Eighth Army campaign in North Africa and reported on the Sicilian and Italian campaigns.

It was natural that the BBC should attach him to Montgomery and his HQ for Operation Overlord, codename for the Allied invasion of Normandy.

"When I went to him with a recording car on the morning of D-Day, he was there in the garden of Southwick House near Portsmouth under the cedar tree," said Frank.

"He was pretty well on his own, receiving messages from the campaign. He said to me, 'I’ve done all my work in preparation for this. I’ve devised the strategy. I’ve worked out the plan. It’s now up to the men on the spot to carry it out'."

Frank’s initial reporting duties included taking a recorded message from Montgomery to his troops.

Then, satisfied there wasn't going to be any action to report on from Montgomery’s immediate entourage, he went off to witness the "miraculous sight" of hundreds of thousands of fighting men who'd been camping in South Hampshire with their weapons and supplies, moving through the assembling, marshalling and transit areas, to the docks, getting on the ships and crossing The Channel to reinforce those who’d already landed on the far side of the beaches.

"It was absolutely incredible to me to see...this great massive movement going ahead so smoothly without any sign at all of confusion or mix up or delay," said Frank.

"Every man, vehicle, weapon, ship and naval vessel was in the right place at the right time. Of course, it had all been rehearsed and timed. Now it was being carried out to perfection."

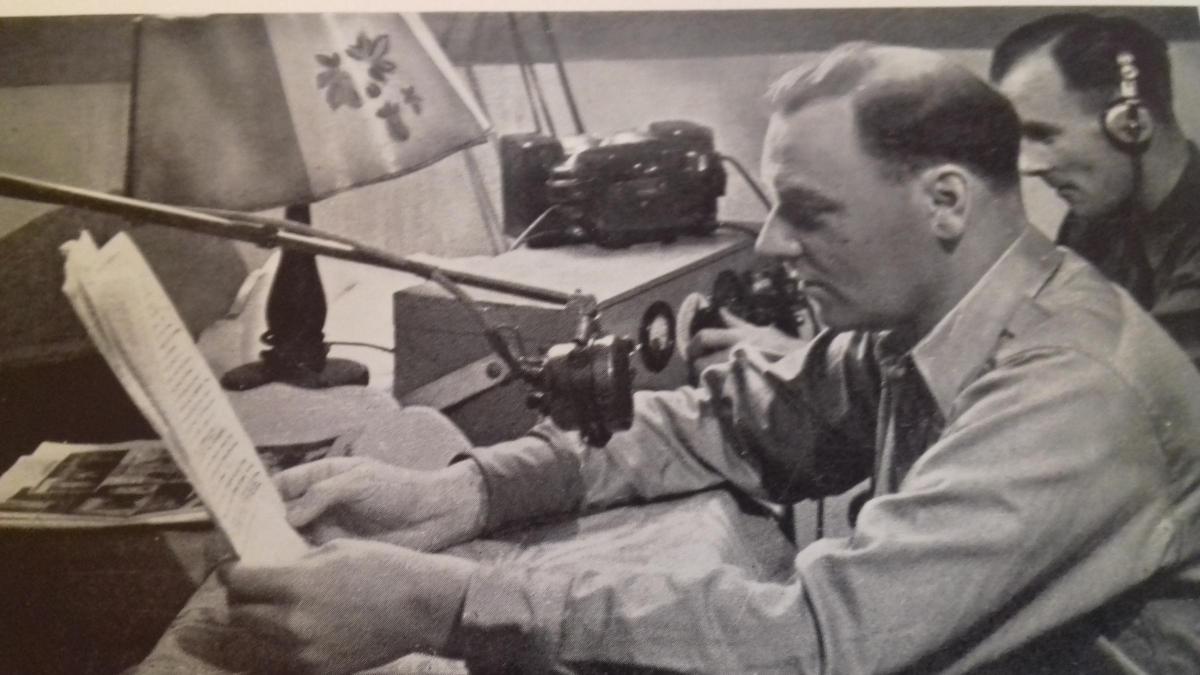

Frank recalled how the BBC team had been supplied with recording apparatus engineers had built for them. After their experience of covering the war in North Africa, Sicily and Italy, they had demanded portable equipment to take into the heart of battle. These were the days before tape recorders, so they had to use disc recording.

"We were carrying around a small portable recording factory in a rather large wooden suitcase," Frank told me.

"When you opened up the lid, there was the turntable, which you had to wind up on a spring. We had to lug enormous disc-cutting machines and a supply of heavy waxed ten-inch discs.

"We had no playback equipment so we didn’t know if we had succeeded in getting a decent recording or not.

"But it was on that primitive, unreliable, fragile instrument that we were able to bring the sound, the pandemonium, the racket of battle, and the voices of the soldiers and the commanding officers, back to people at home by their firesides in Britain and out to the world so that at least the listening audience could form a sound picture in their minds of what it was like really to be in the front line and facing up to the enemy."

The BBC had 27 correspondents at D-Day, with reporters on every beach and with gliders, naval ships, air attacking forces - one reporter even jumped with the Paras.

Frank added: "I got there on the third day. Men, supplies and equipment were pouring ashore all the time, all along the beaches, but the scene itself looked to be one of total confusion at first.

"There were huge heaps of wreckage everywhere. All the obstacles and defences the Germans had created to keep us away from the beaches had been torn up and were lying around in great heaps.

"I especially remember the huge coils of barbed wire our engineers had stacked up – great mountains of the stuff which had been intended to hold us back but which we’d cut through and overcome.

"I also remember the trackways which had been opened up for us on the beaches which were lined with white tape on each side, warning us that we had to keep within those trackways because the beach mines had been lifted up and movement was safe in those lanes. But once you crossed the white ribbon and you were in the minefield, you were in trouble.

"When you looked around, there was the whole armada of ships bringing in the supplies and reinforcements but in the forefront was the wreckage of ships which had suffered the earlier landings, some of them overturned, some of them lying on their sides and several abandoned.

"It was a scene of organised confusion but it was a scene also of great success."

The French people were mixed in their reception of the soldiers. Montgomery said to Frank a few days after landing: "Do you really think the French wanted to be liberated?"

The people of Normandy were unhappy because their homes were being destroyed and they had to leave.

For the most part, though, the French were overjoyed and ran out of their houses in the countryside as the columns passed. They brought out lumps of butter wrapped in cabbage leaves and bottles of Calvados and wine.

The BBC demanded staff should be honest in their reporting, while for the Germans, everything was acclaimed as a great victory even if it wasn’t.

"In our case, our instructions were quite clear – we told the truth," Frank said. "If we suffered a reverse, we said it was a reverse. If it was a success, we reported it as a success. This established the BBC’s credibility very firmly with its vast audience at home and overseas."

Frank took his chances on how he got his reports – often recorded under fire – back to London. He’d give them to couriers heading to the capital but, after landing strips were laid, sent them by air.

These are Frank Gillard's words in his dispatch on June 6, 1944: "Up on the tiny flag deck a senior naval officer stands beside the skipper, a microphone in his hand. Behind him is the trumpet of his loud hailer.

"It’s coming up to time. Not zero hour yet, but zero hour minus. The moment when the assault craft are to set off from their assembly area for the beaches.

"Astern of us, the assault craft have assembled. You know that they are neatly marshalled there, in formation, but you can only make out the leaders. The loud hailer checks them over. Voices reply faintly out of the darkness.

"The Naval Commander is looking at his watch. He puts the microphone to his mouth. 'Off you go then – and good luck to you'."

One of Frank’s unusual duties was to organise an open-air church service from the Normandy beachhead, which the religious broadcasting department had requested.

As senior BBC correspondent on the Continent, Gillard was present at all the major events after D-Day, including the Fall of Caen, the Battle of the Falaise Gap, the entry into Eindhoven, the advance to Nijmegen and the first advances into Germany.

After joining General Omar Bradley’s Army Group, he became the first person to break the news to the world of the link up of Eastern and Western Forces.

At 6pm on April 27, 1945, Gillard came on air at the BBC in London and famously told listeners: "East and West have met."

On the nine o’clock bulletin, his dispatch that was followed by messages from Churchill, Truman and Stalin. Such was the respect in which Frank Gillard was held that he was invited by Monty to fly with him to Berlin to witness the signing of the Armistice agreement by the four great powers.

Frank showed me the cheque he received from Montgomery in settlement of a bet on the date of the end of the war. Frank Gillard later became managing director of BBC Radio and a member of the board of management. He died in 1998.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel